There are paintings that push beyond the confines of their chronology, with auras that have little to do with the orderly genre from which they emerge or even the painters who painted them. Obliterating the frames around them, they break through the fourth wall, headed straight for the viewer’s psyche like a parasite—settling into that part of the mind where we read and recognize ourselves.

I chanced on one of these wonders a few weeks ago—the portrait of Hans Burgkmair the Elder and his wife Anna, painted in 1529 by 24-year-old Lukas (Laux) Furtenagel. Burgkmair was 56 at the time, a successful printmaker and painter in Augsburg, a financial center of the Holy Roman Empire. He was also a friend of Albrecht Dürer, who had died a year earlier.

Before we’ve even had a chance to gawk at the two skulls bulging through the mirror’s own fourth wall, we feel eerily close in time to this couple. They loom from the darkness as if illuminated by a naked lightbulb, not the kinder, gentler glow of candles. Their facial features have not rearranged themselves into the banal neutrality typical of posed portraits—of any era. They are looking at us with sad resignation.

It is as though we have opened the wrong door along a hotel corridor, and caught a couple not in flagrante, but in an intimate, sudden confrontation with their mortality, brought on by events we know nothing about.

The Burgkmairs look like refugees from a more recent era, a bohemian art-world pair troubled by the inevitable. There’s not much about her dress that says Renaissance housewife. More astonishing, her red hair is loose, not covered by a snood or a cap, as in formal portraits of the period. Hans wears his artist’s cap, but is sartorially more bourgeois than we’ve ever seen him. I couldn’t help thinking of Christo and Jean-Claude with her red hair, a pair always together. But those two smiled all the time, at least in public, and Christo hardly ever bothered to dress up.

Burgkmair was at the end of a social climb that had elevated him from artisan to artist favored by Emperor Maximilian I, who awarded him an insignia and ring for his services. Laux Furtenagel, the double portrait’s painter, was at the beginning of a career that never materialized.

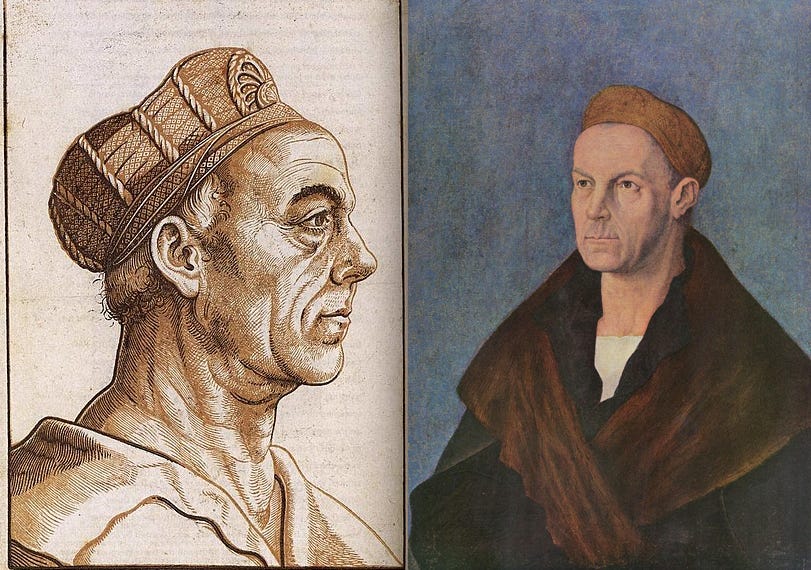

While Hans Burgkmair the Elder is still respected enough to share billing with Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Elder in a recent Kunsthistorisches Museum exhibition in Vienna, there’s a yawning gulf between Dürer’s genius and the journeyman career of his friend Burgkmair, whose CV reads like a pale rhyme of Dürer’s:

Only two years apart in age, both were drawn to study with master engraver Martin Schongauer in Colmar (Dürer arriving after Schongauer’s untimely death). Although Burgkmair studied with Schongauer for several years, he is known to have made only one engraving.

Both made pilgrimages to Italy that influenced their work.

Both worked on woodcut projects for Emperor Maximilian I.

Both portrayed the banker Jakob Fugger, whose wealth by today’s standards would be around 400 billion dollars. (Sorry, Elon, 314 billion just doesn’t cut it.)

Both made woodcuts of the famous rhinoceros given to the King of Portugal. (Dürer’s was made a few months before Burgkmair’s)

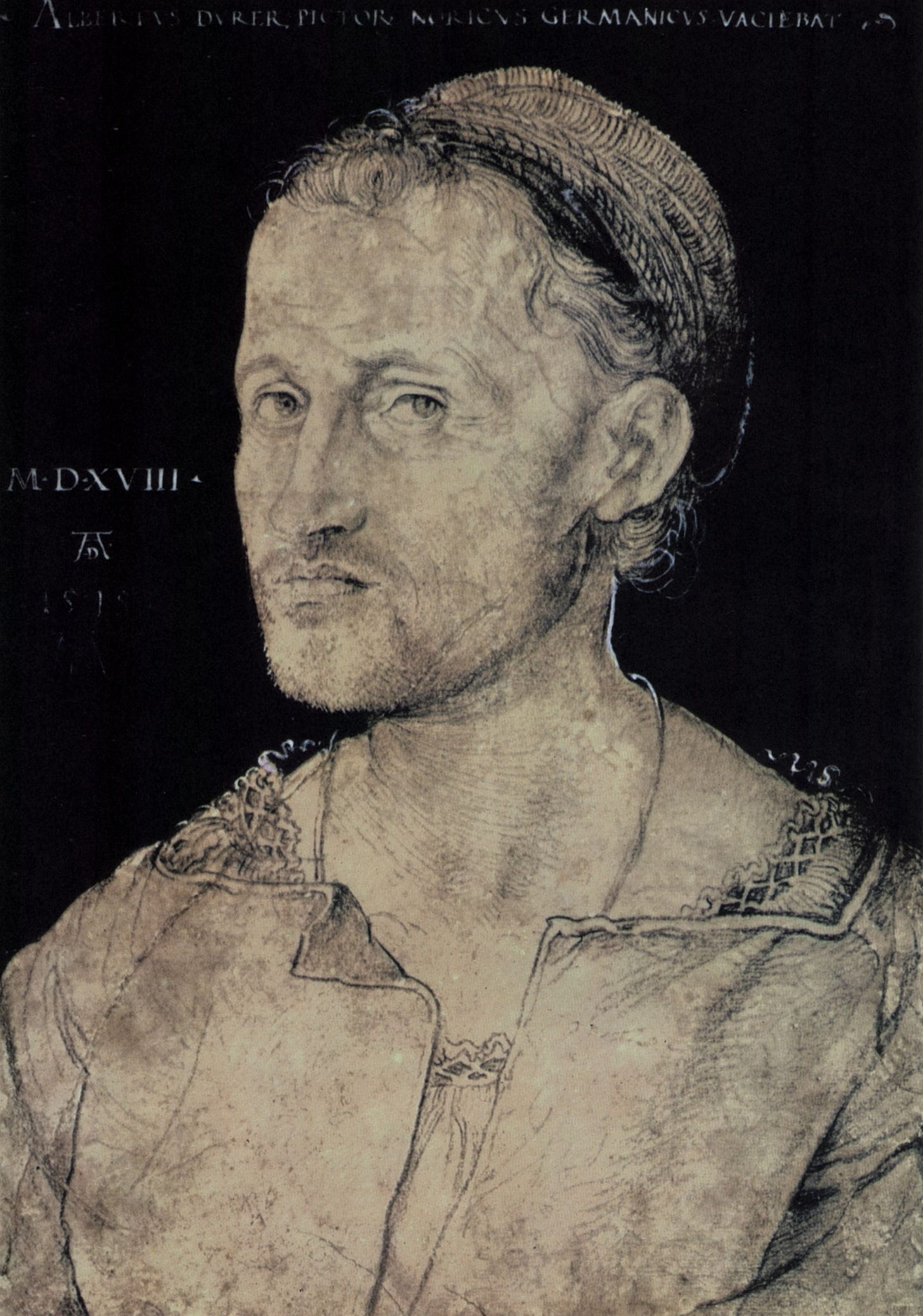

Dürer made a charcoal, ink and ceruse drawing of Burgkmair, who allegedly made a drawing of Dürer as well, which seems to have been lost.

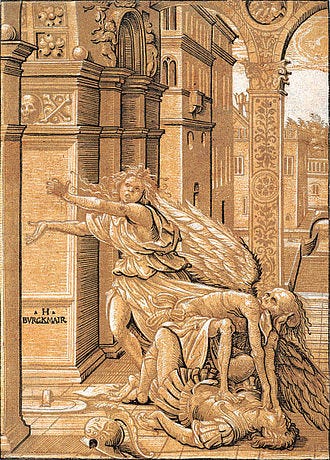

Posterity’s reception of Burgkmair’s work might explain why he is better remembered for the double portrait—which he didn’t even paint—than for anything else. With the exception of one spectacular woodcut, Lovers surprised by Death, which introduced his innovations of chiaroscuro woodcuts (using two or more blocks of different colors), much of his work is easily forgettable—well-crafted but lacking in imagination.

If there’s a star to be born in this story it is the mysterious young Lukas or Laux Furtenagel, whose authorship of the painting came to light only in 1933, when restoration work revealed his name as the painter. Until then, it had been thought to be a self-portrait by Burgkmair—although anyone familiar with Burgkmair’s paintings should have seen that there was no way Burgkmair could have painted this double portrait. He wasn’t talented enough. Only after the fact did Nazi art historian Ludwig von Baldass admit in 1936 that “the conception is new and bold and has no parallel in German art.” This painting, he said, “places Laux Furtenagel into the ranks of the great German portrait painters.” 1

Since then a dubious theory has been adopted by the Kunsthistorisches Museum and other institutions, that the painting is Furtenagel’s copy of a Burgkmair work, now lost. But if Burgkmair had painted a version himself, why did he ask an artist half his age to paint a better copy? Maybe that’s the point: I think Burgkmair would have known his own version (if there was one) wasn’t good enough. (A Rontgen of the work revealed no other version underneath, not even preparatory sketches.)2

It takes two, or in this case three, to make a portrait: the subjects and the painter. It’s clear that the painting was staged—or at the very least, agreed to—by Burgkmair and his wife. That would make this allegorical work a dialectical collaboration between a youth and a couple more than twice his age who are moving closer to their mirror selves with every passing day. (Burgkmair died two years later.)

Both Burgkmair and Furtenagel were Lutherans in a divided Catholic city. The French historian Marianne Bournet-Bacot rightly suggests that this is a new kind of religious painting, a protestant one.3 Gone is the fussy imagery of Catholicism—the dei ex machina, the winged babies. Instead we have an inscription on the mirror’s edge ‘Recognize thyself’ and on its handle ‘Hope of the world’ —suggesting redemption through faith alone, a key point of Luther’s theology.

Laux Furtenagel has been rescued from obscurity, and with good reason. But time is not kind to historical research initiated so long after the fact. Fires, floods, wars, carelessness, and possibly even malice have destroyed evidence; secrets have been taken to the grave; events have been suppressed. What we know of his life suggests that he was a prodigy, beginning his formal studies at the early age of 10. The eldest son of a painter, he was primed to take over his father’s atelier after his death. This did not happen. What did?4

A linden wood medal reveals a handsome 22-year-old, dressed in finery no artist would be wearing at his age unless he was a master. (Or was he simply a model for the medalist?) Was his talent already recognized? If so, where is the rest of his work?

Not being an art historian, I can indulge in some speculative fiction: I suspect that some scandal subsequently drove Furtenagel away from Augsburg, and that his work up to that time might have been destroyed or hidden away. His only other well-known work is the 1546 preparatory sketch of Martin Luther in his coffin, which compares favorably to Lucas Cranach the Elder’s own cartoonish version.

In his one masterpiece, Furtenagel’s grasp of painting technique leaps over centuries, infusing this Renaissance work with something close to a neue Sachlichkeit (new objectivity). Here we see people so real, so perfectly imperfect, their faces expressive to a degree hardly known at the time. The existential sorrow written on their skin recalls a complicated modern time closer to ours than to theirs.

The Burgkmairs must have known what Laux was capable of when they let him into their private sphere of anguish and looked him (and us) straight in the eye. Furtenagel was no copy boy, but their artist of choice for an unforgettable memento mori.

Something else prevented Laux Furtenagel from fulfilling his genius. We can’t rewrite history, but we can grace him with our awe and amazement.

Gert von der Osten Lukas Furgenagel in Halle, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, Vol. 34 (1972), p.106

Gert von der Osten Lukas Furgenagel in Halle, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, Vol. 34 (1972), p.115-117

Marianne Bournet-Bacot Lucas Furtenagel (Augsbourg, 1505-avant 1563), peintre luthérien, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 77. Band /2014, p. 58

A special shoutout to Marianne Bournet-Bacot’s above mentioned article (footnote 2), which provided more biographical information about Furtenagel than I was able to find anywhere else.

Beyond the confines of chronology kind of sums up how I'm feeling at my age...

Wonderful essay and painting. How interesting that the couple agreed or proposed to be painted in such a revealing fashion. I love the hand extended toward the viewer, as of the subject is about to tell you something.