Interior Landscapes

The colorful imagination of Félix Vallotton

Sometimes it pays to spend more time in the detours of art history—leaving behind the rigor mortis of the canon to follow new pathways—not necessarily toward an alternative canon, but to discover forgotten artists deserving of more attention.

The half-century of art between 1880 and 1930 was explosively innovative, with a burgeoning middle class now taking up the joys of painting, birthing multiple new ‘isms’—painters extricating themselves from the myopic, bourgeois poetry of impressionism and probing in all directions with anarchic glee, as they tried to find their single voice within the noise of impending modernism.

One of those painters was the Swiss artist Félix Vallotton. For reasons that I am still trying to figure out, I have fallen for the works of Vallotton, not a household name in art history, but one of the most perplexing and intriguing artists of the period. There is no nutshell to reduce him to, no ‘ism’ to give him a lasting home (the Nabis were more of a brotherhood), no one specific style to make him recognizable, no pathology to explain his subject matter (500 nudes) or his drive (nearly 2000 works). As an innovator of woodcuts, he recalls the duality of Dürer’s oeuvre. As a landscape painter from memory, he oddly echoes Caspar David Friedrich, although their styles were miles and almost a century apart.

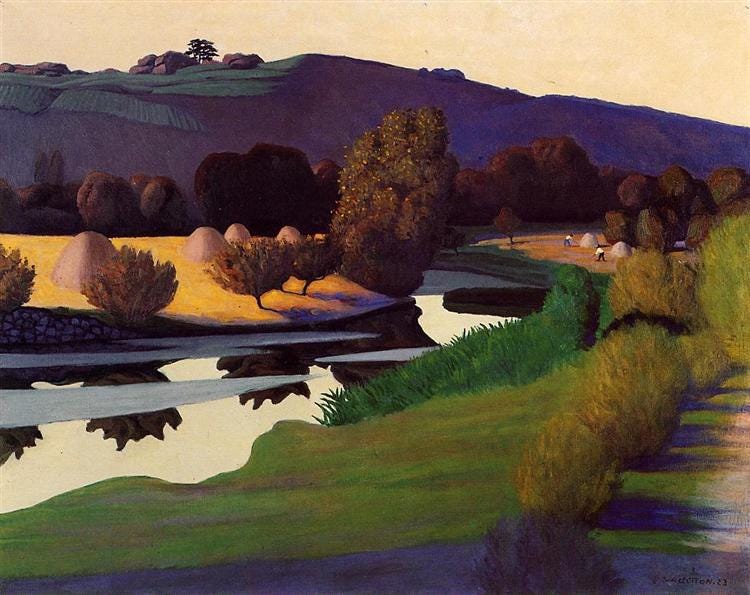

“I want to construct landscapes entirely based on the emotions that they have created in me, a few evocative lines, one or two details, chosen, without a superstition of the exactitude of the hour or the lighting.”

Friedrich was more exacting in the details, but the impulse to rely on one’s inner eye makes curious brothers out of two distinctly different personalities.

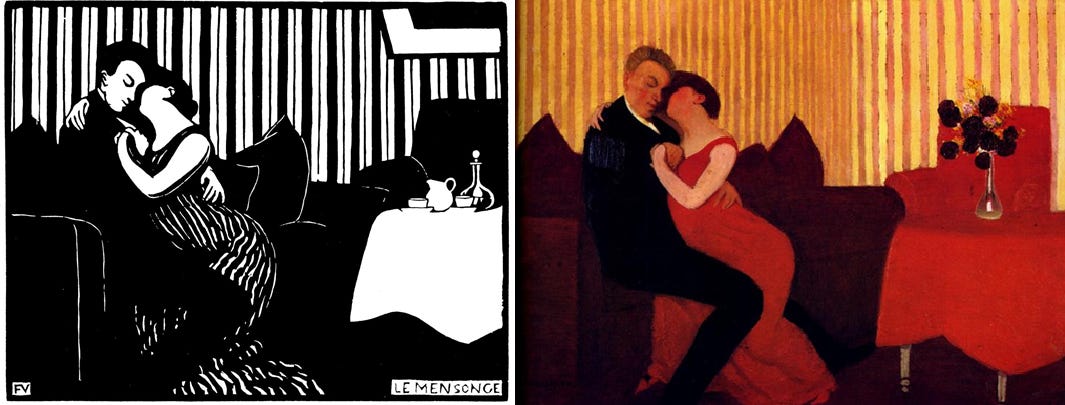

Vallotton may have plied the pastoral byways of nature, but his preferred loci operandi were the interior landscapes of the Parisian bourgeoisie. In a satirical series of woodcuts called Intimacies, he exposed the amorous subterfuges of high-end adultery in stark black-and-white prints where black is the dominant, all-consuming shade. Starring ‘it’ femme Misia Sert as his alleged model, the series was printed in her husband Thadée Natanson’s anarchist publication La Revue blanche, where it became an instant success.

Whatever transpired, or didn’t, between Vallotton and his model, there was enough left over to inspire a set of dazzling paintings whose remarkable colors amount to a chromatic vocabulary of passion, in all its deliciously claustrophobic, hothouse hues—from the darkest purples, blues and roses of smoldering attraction, to the flaming reds of a lie. Seeing how these colors mesh from painting to painting, one discovers a language of love in them—a palette more evocative of emotion than of place.

Not the typical interiors of the bourgeoisie, they are the upholstered vessels of intimacy invented by Vallotton himself, with conspiratorial colors and textures brought together symbolically. Most were painted in the year leading up to Vallotton’s marriage to the widowed daughter of art dealer Alexandre Bernheim—often called a marriage of convenience, but still a genuine love story, if a letter Vallotton wrote to his brother is to be believed. Whether the intimate paintings of that year reflect a lingering weakness for Misia or a passion for his fiancée Gabrielle may never be known. Vallotton, who kept a life-long journal, later expurgated everything prior to 1914.

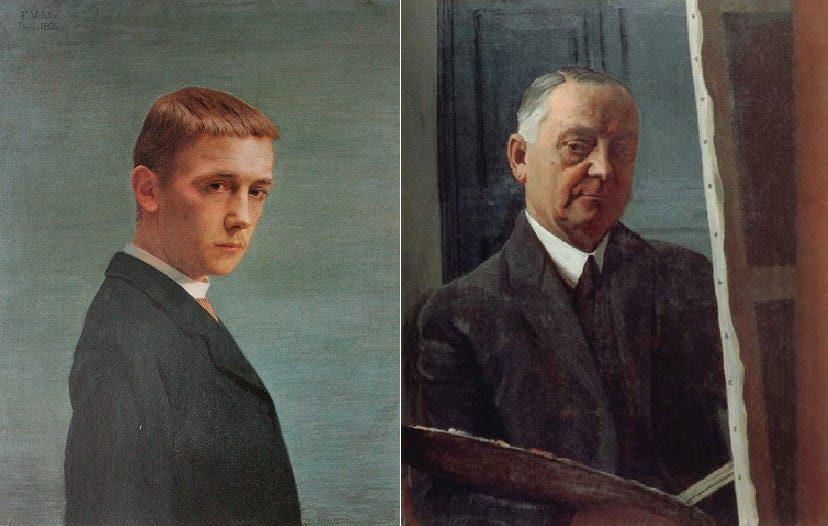

When I like a painter’s work, I try to invade his persona, try to see the world through his eyes, explore his private history. Vallotton doesn’t give away much. A self-portrait at 20 shows him to be a wry observer rather than a passionate partaker. That sidelong glance—a look that might see right through you—will continue throughout the self-portraits, never revealing the man but suggesting intense scrutiny behind the blandness of his pose.

His was not the artistic temperament of a Picasso or a Van Gogh. Vallotton rarely let emotions show, but if his three novels1 are any indication, there was magma flowing just below the staid Swiss surface—in engaging narratives that hint at aspects of his personality no friend or contemporary would have guessed. They reveal a vivid imagination, a wry humor and a perplexing inner turmoil that may have emerged from undefined guilt. As one might expect, his physical descriptions are detailed, almost painterly. But his ease with emotional narrative is wholly unexpected and sets his fictional work apart from his art. Still, as he did in the woodcuts visually, in the novels he critiqued society with bulls-eye efficiency: “The decay of conversations is often such that the mere fact of opening one's mouth becomes meritorious and counts for you.”

The woodcuts made him famous in the last decade of the century, but when marriage made it possible for him to devote his time solely to painting, his reputation grew as he surfed from one -ism to another, without ever venturing more than a few steps into into modernist or abstract terrain. He had begun in realism and dabbled in a combination of symbolism, magic realism, post-impressionism and cartooning. He could be ponderous or whimsical, depending on his mood. Indeed Vallotton’s minor status in the history of art may be a side effect of his perpetual self-reinvention.

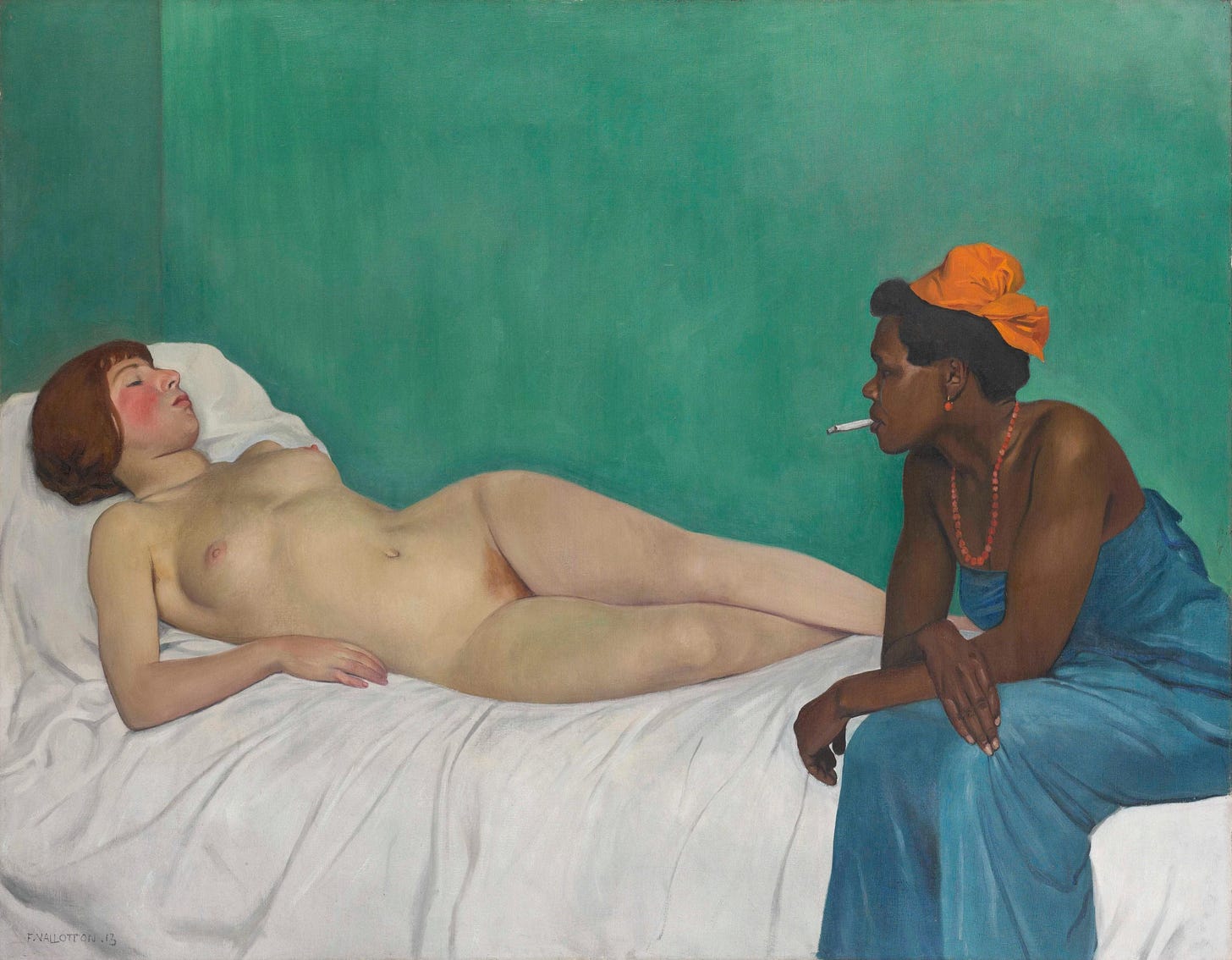

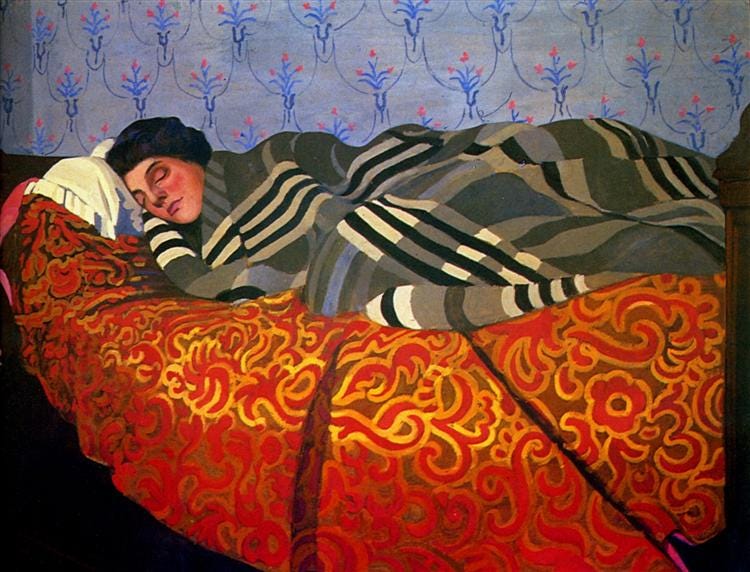

About those nudes: The British writer Julian Barnes, a qualified fan of Vallotton, believes that most of his nudes are ‘dreadful’, penning a new “Vallotton's law: that the fewer clothes a woman has on in his paintings, the worse the result.”2 Some of them do seem contrived, but I suspect Vallotton was deliberately exploring different styles, as he was wont to do, and sometimes painted from memory. His best nudes presage the Neue Sachlichkeit, especially Sleep or his nod to Manet’s Olympia called La Blanche et La Noire. What Barnes called ‘inert’, I would call marvelously deadpan. (Oddly, Barnes seems to approve of the whimsical cartoon nudes of Vallotton’s 1892 Bathers on a Summer Evening, with its nod to Lucas Cranach’s Fountain of Youth.)

Any doubt about Vallotton’s ability to paint a female nude could be countered with his first known painting at age 19, Étude de fesses (A Study of Buttocks), the most perfect close-up of an imperfect fanny in history.

I find myself always returning to his landscapes, their blocked colors rewriting the terrains of his memory. Evening on the Loire (1923) somehow improves on nature by replacing verisimilitude with a gorgeous stage-set version of landscape.

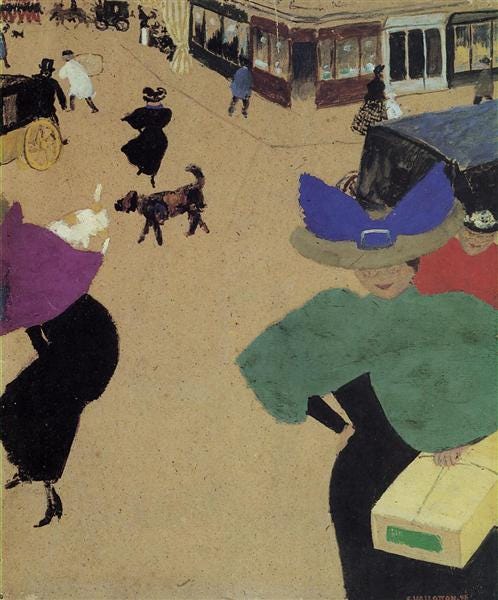

It is often Vallotton’s choice of subject that makes his works memorable—even more than the style in which they were painted. Verdun (1917) is a bit too beautiful for war, too ordered in its execution, and yet powerful. Le Ballon (1899) or Sleeping Woman (1899) or Box Seats at the Theatre (1909) or Street Corner (1895) are unforgettable for their capture of moments no one else would think to paint.

Vallotton may have been a man of few emotions, but the canvases tell another story, one that deserves its own ‘ism’ (Vallottonism) if art history ever gets a rewrite.

La Vie Meurtrière, Les Soupirs de Cyprien Morus, Corbehaut

A favourite of mine. Thank you for this.

I’m not familiar with this distinctively fascinating painter. His use of color is riveting, particularly in the landscape and in “Intimacies,” which resembles a play in paint.