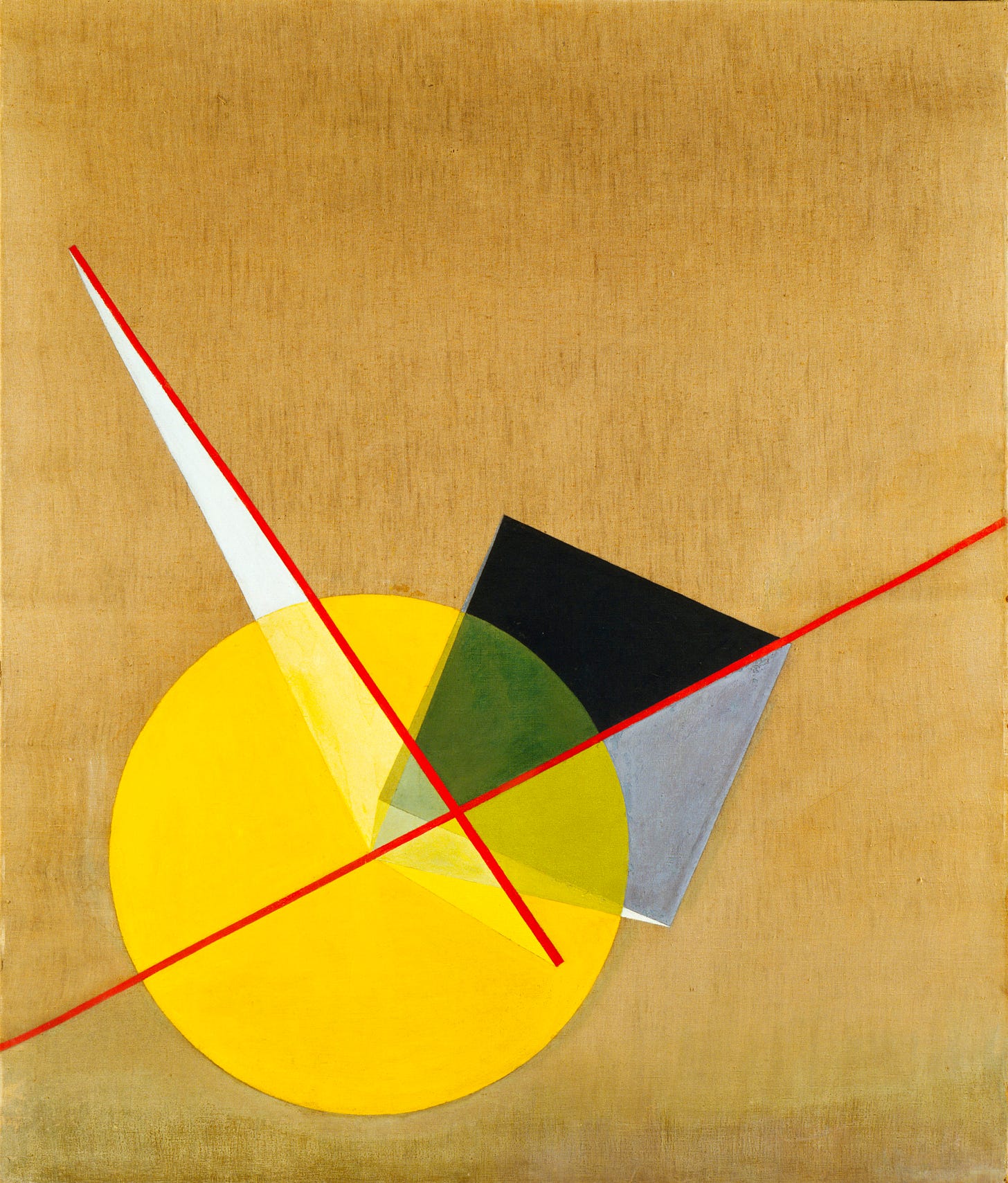

When I first moved to Salzburg, I rented a place in a small 19th century building around the corner from the medieval Linzer Gasse, where Renaissance polymath Dr. Paracelsus was buried, and where Expressionist poet Georg Trakl had worked in a pharmacy. The flat had high ceilings, tall windows, a lovely old herringbone wooden floor, and blinding white walls just waiting for works of graphic impact to give them a semblance of meaning. I couldn’t afford a painting, but in a nearby poster shop—they were popular in those pre-online days—I flipped through hundreds of art reproductions, hoping to find an image deserving of those pristine walls. Only one poster fit the bill: a László Moholy-Nagy collage from 1922: Kinetisch-Konstruktives System (KKS).

László Moholy-Nagy is best known for his years teaching at the Bauhaus in Dessau and for bringing the Bauhaus school to America—to Chicago where it eventually became the Institute of Design. Born in Hungary in 1895, he hadn’t planned to be an artist, having studied for a career in law. But sketches he made to document his experiences as a soldier in World War I changed his mind.

My knees grow weak at the sight of geometry. I begin to slip in and out of faux spaces—exploring interiors of cubes, winging my way around spheres or careening through diameters. Something about Moholy’s yellow cylinder was leading me somewhere with clear kinetic energy. I couldn’t stop looking at it, encouraged by a newfound respect for deep yellow, a touch of blue and a pinch of red. The arrows pulled me left and right, the directions suggesting a whirling dervish energy that I could feel inside.

KKS didn’t depict an object one could pin a name to, but it moved—both transitively (me) and intransitively—as it launched from the poster into my imagination every time I saw it. Moholy wasn’t interested in garden imagery, still lifes, hazy landscapes, or bourgeois femmes. The form, whatever it was, was abstract and unaccompanied—on a trajectory to the edge of the paper and beyond, taking me with it. I was glad to give it wall space.

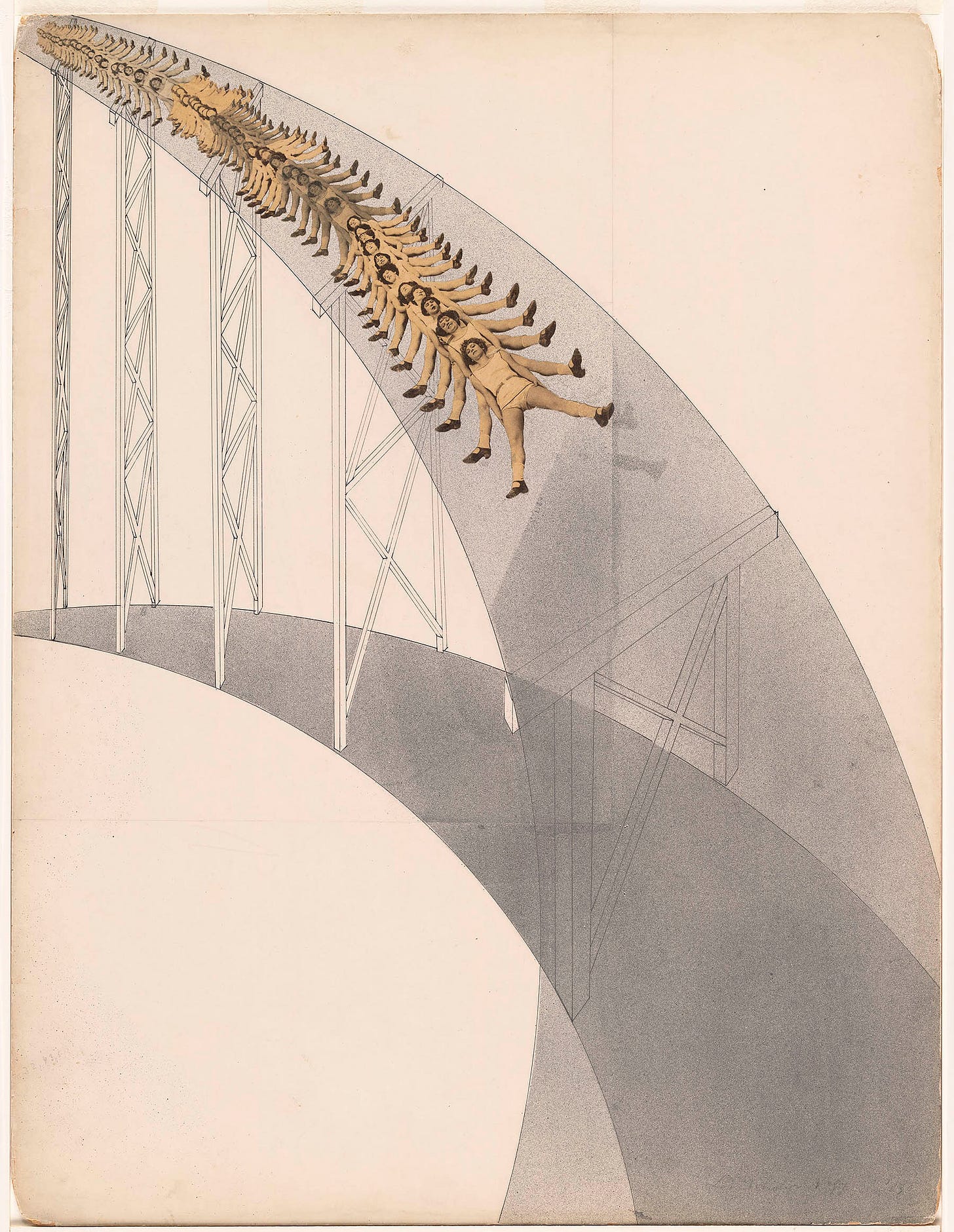

Much later, I found out more about this work, and how important it had been to Moholy’s grand vision for the future of art. In 1928, together with fellow Hungarian István Sebök , he returned to KKS, this time with a proposed reorientation for art that would erase the barrier between artist and observer, visualizing a vertical tower to challenge all previous notions of aesthetic experience—with emphasis on ‘play’ in both its theatrical and amusement-park connotations.

In his somewhat abstruse manifesto in the magazine Der Sturm in 1922, he asserted that what he called “vital constructivity” would lead to the “Dynamic-Constructive Energy System, whereby a person, up to that point merely receptive in his observation of works of art, experiences an intensification of his capabilities like never before, and himself becomes an active factor in the unfolding energies.”1

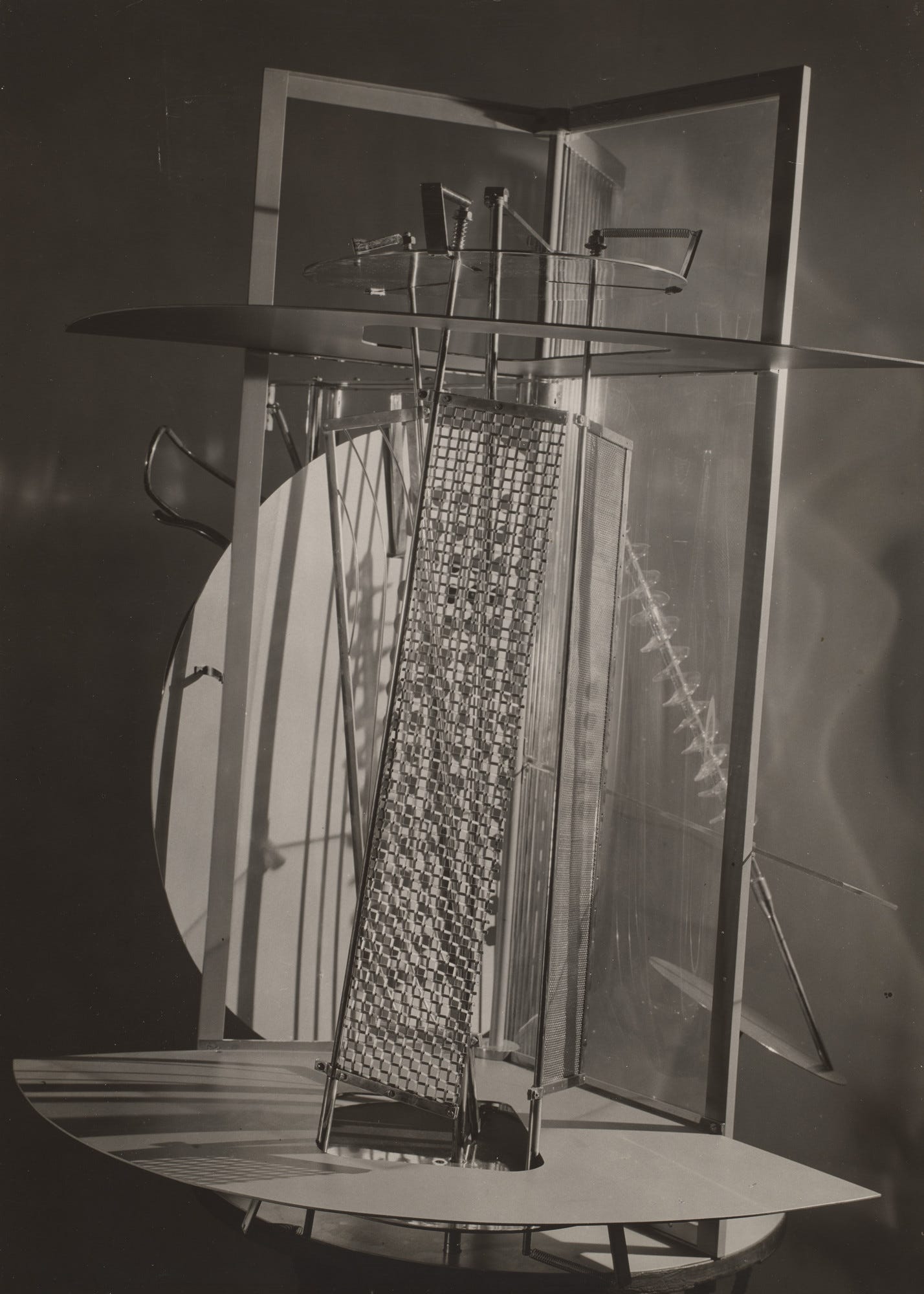

Like his fellow constructivists and related suprematists, Moholoy-Nagy was after more diverse interactions with imagery. His was a synaesthetic kind of art: Among other things, he brought light together with a reflective three-dimensional moving structure to create a bold third rail of artistic impact—the kinetic light sculpture, or what he called ‘vision in motion’, which yielded a panoply of shadowy imagery in all directions. Considered his masterpiece, The Light Space-Modulator (1930) (aka Light Prop for an Electric Stage) managed to be an object of stunning intrigue on its own—with or without the kinetic delivery of luminous magic to the walls around it.2

Moholy’s vision fit the Bauhaus ethos perfectly: A redefinition of space within and without, accompanied by an extension of artistic endeavor beyond the accepted norms.

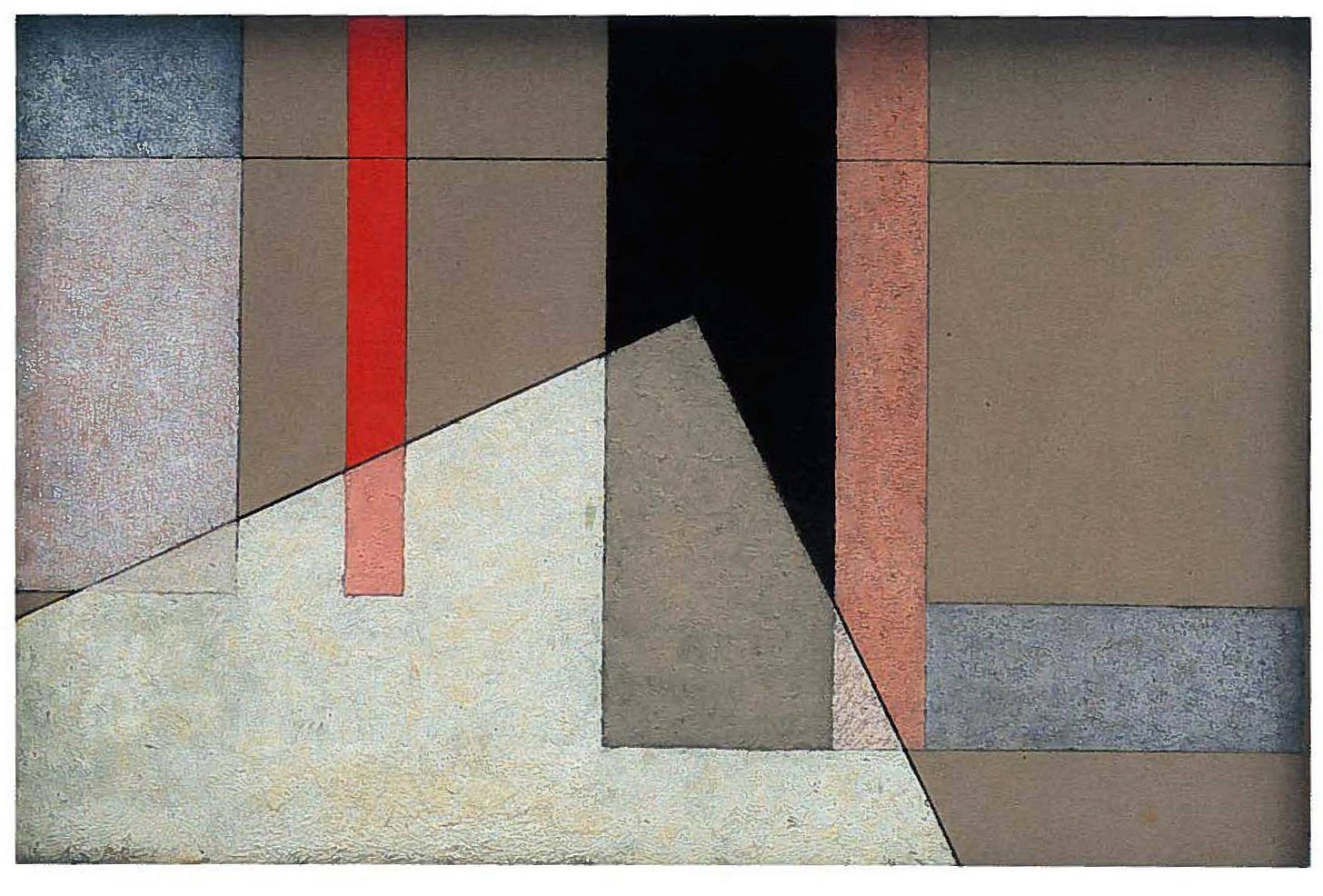

In his paintings and collages Moholy could transform a two-dimensional image into 3D through colors and shades alone—with such breathtaking accuracy that it’s easy to slip into the implied space between two intersecting semi-transparent planes. Stare at a Moholy-Nagy painting for a while and you’ll begin to feel dizzy from an emerging 3D awareness. 3

Dizziness and disorientation were the order of the day among the Cubists, Constructivists and Suprematists—and they figured heavily in Moholy’s view of art.4 Moving in tandem with Kazimir Malevich’s non-objectivity and his friend El Lissitzky Proun period, Moholy envisioned art as occupying spatial, theatrical dimensions that invited participation. He wanted to reinvent the aesthetic experience itself.

As a visionary, experimenter, and man ahead of his time, Moholy was dazzling. But in the end, it’s the paintings and collages that anchor him to the canon.

There exists a special set of emotions that emerge only in the presence of abstract art, rare ones that dwell in wordless recesses of the brain where stories, explanations, or definitions cannot reach them. Abstract art makes contact with them. Sometimes it’s colors that lure these hermit feelings from their cerebral caves; sometimes it’s an arrangement of forms never before seen, without meaning or content. Malevich called it “pure artistic feeling”—unrelated to figurative, depictive art.

Moholy’s paintings and collages have that power, Rothko had it, Richter has it. Moholy-Nagy’s relative obscurity as an artist may owe something to the public’s undying preference for representational art, in whatever form that takes. (I saw far too many Monet water lilies in that poster shop, and began to feel nauseous from an overdose of intended ‘loveliness’.)

One aspect I find intriguing is his obvious love of the diagonal—immediately apparent in both KKS works, but plentiful throughout his oeuvre. He wasn't alone in this, but exceptional. A separate essay could be written on the power of the oblique, especially that 23.4° axis tilt we inhabit here on Earth.

We now live in a time of obliquity, the ‘diagonal’ a metaphor waiting to be exploited as we navigate a society of ‘leanings’, including the political and philosophical. An oblique line on its own can suggest that something is askew, or not quite right. But it can also be aesthetically powerful. Moholy’s use of it is propulsive, dynamic, kinetic—a force that defies vertical-horizontal predominance.

This may be what inspired me to photograph my dining room table and chairs obliquely, channeling familiar Bauhaus shadows and recalling the Kinetisch-Konstruktives System that had hung on my wall all those years ago.

Postscript: Around 1970, I met Moholy’s widow, the art historian Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, at an event at the Architectural League of New York. Those were troubled times, when violent police crackdowns on anti-war protests on college campuses had led to a number of student deaths. In a thick German accent, the imposing woman declared that the US was beginning to look more like 1933 Germany. Not surprisingly, I replied, ‘That could never happen here.’

The Pleasures of Sensory Derangement and Its Uses in the Art of the Early Twentieth Century Avant Garde. Oliver A I Botar. I am indebted to this exciting paper by Dr. Botar, Professor of Art History at the University of Manitoba. Not only did he broaden my knowledge of the various art movements of the period, but he also provided the most cogent translation of the quotation from Moholy’s article in Der Sturm (1922), titled Dynamisch-kontruktives Kraftsystem.

The Pleasures of Sensory Derangement and Its Uses in the Art of the Early Twentieth Century Avant Garde. Oliver A I Botar. (See footnote 1)

New to this artist & such an informative piece!!! Ty!!

This is fascinating, Brooks, and I loved your own photos that you included!