About Face!

The Growing Allure of the Rückenfigur

No, this is not about ‘face’, of which we have more than enough coverage—artistically, commercially, cosmetically and every other which way. No, this is about the other side of the face, the ‘about-face’ immortalized by German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, who turned 250 today. It’s about the Rückenfigur, for which we still don’t have a decent English translation even though it’s a visual device that is making its way into our media toolbox as an antidote to the tedium of the forever frontal view.

Just look in the Guardian this week, for a series about friendship. Or the Frankfurter Allgemeine a few weeks ago, for an article about early retirement:

What editors and art directors are beginning to learn, Friedrich learned two centuries ago: that there’s information to be gleaned from a person’s back—attitude, intent, mood, emotion and awe—even if, or especially if, that information is vague.

Many have cited Friedrich’s alleged middling talent for drawing faces as a reason for his use of the Rückenfigur.

Friedrich wasn’t interested in faces. He was after something else—social confirmation of the emotional, spiritual and aesthetic power of nature. For that he often provided a conduit—a human response to that power. He wanted to prove that the moon wasn’t just there to light one’s path in the dark, it was there to be gazed at— with awe, curiosity or enchantment. The men and women who people his canvases are his evidence. Drinking in sunsets and moonrises, they confirm the Romantic sublime.

As viewers of his paintings, we are facing in the same direction as the Rückenfiguren. This simple connection invites us to share their experience, just as he invited them into his painting to share his experience.

What may now seem obvious about nature’s empowering effect, once needed someone like Friedrich to emphasize and legitimize it. The young Romantic poet Novalis understood this: “To romanticize the world is to make ourselves aware of the magic, mystery and wonder of the world; it is to educate the senses to see the ordinary as extraordinary, the familiar as strange, the mundane as sacred, the finite as infinite.”

But where did Friedrich get this idea of the Rückenfigur? Was it solely his idea? I think not. In researching the period in 1810 when he went on a hiking tour in the Giant Mountains with his friend Georg Friedrich Kersting, I found two drawings by Kersting that show Friedrich himself as a Rückenfigur.

In the first one it looks as if Friedrich has been sketched unawares. He is kitted up for his trek, with painterly tools and folded easel strapped across his back.

The second drawing is odder and more significant. Friedrich sits atop a rock that looks eerily like the rock he stands on in the 1818 painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog—sitting precisely in that cleft where his left foot is placed in the painting. He is looking out over a panorama and seems too absorbed to notice that Kersting is drawing him from below.

I’ll probably be trounced by art historians for suggesting that Friedrich was inspired by Kersting’s unobtrusive drawings of him on their 1810 tour. But my theory doesn’t diminish the brilliant use Friedrich put to such back-view depictions. Looking over his work chronologically, Friedrich had painted only one serious Rückenfigur before that tour, in a completely dull urban setting (By the Town Wall, 1800), without any reference to nature.

Could it be that Kersting inspired Friedrich to see the Rückenfigur in a different way, in the way Kersting had used it when he captured Friedrich looking at nature from that rock?

Kersting’s 1810 drawing hints at another significant aspect of the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. In the drawing, Friedrich is sitting safely on the rock, not daring to stand up. In Friedrich’s 1818 painting, he boldly stands on that same precipice, undaunted by the risk of falling off.

1818 may have been the happiest year of Friedrich’s life. He had just gotten married at age 43, ending decades of solitude and bachelor living. Domestic bliss, love for another, the promise of children—all were completely new to Friedrich.

To my mind, this is why he painted, for the very first time, such a prominent Rückenfigur. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog was a declaration to the world that he was ready to face that new, indeterminate and foggy future spread out before him. In that same year he painted a second prominent Rückenfigur, of his new wife at sunrise, a variation on that indeterminate future that is filled with hope and optimism.

Spend a little time with Friedrich, and you’ll notice a lighter side of his personality . In an 1801 drawing of the Rock Arch in the Uttewalder Grund, a delightful father and son seem to be dancing—miniscule against the overwhelming rocks above them. Their body language reads jazzy, as though they might even dare the rocks to fall. A similar motif shows up thirty years later in The Evening Star, 1830—Friedrich’s son dancing to a sunset. Joy is the word that comes to mind, as though an extra dose of Romantic sublime could turn anyone into a ‘dancin’ fool.’

Friedrich’s Rückenfiguren come in all sizes and degrees of detail. Some are rough brushstrokes, some are mere pixels in the distance and one pair is almost invisible: the rowers in his 1807 proto-Turner Fog .

One painting stands out for its rare frontal figures, two men who ignore the wild beauty of the night, preferring comradery and the warmth of a fire. Friedrich is pitting his own obsession with the sublime against the cozy glow of a social moment. The painting reflects this dichotomy by offering two equally exquisite sources of light.

Now that the art world is focused on Friedrich this year, it may be time to seriously consider a proper English equivalent for the word Rückenfigur. I have a suggestion: The word ‘rucksack’ for backpack or knapsack has sailed into the English language without incident and without its old umlaut. Why not follow suit with the word ‘ruckfigure’, (anglicizing ‘figur’ and using the same ‘ruck’ as in ‘rucksack’). Just saying.

Finally, to descend from the Romantic sublime to the present ridiculous:

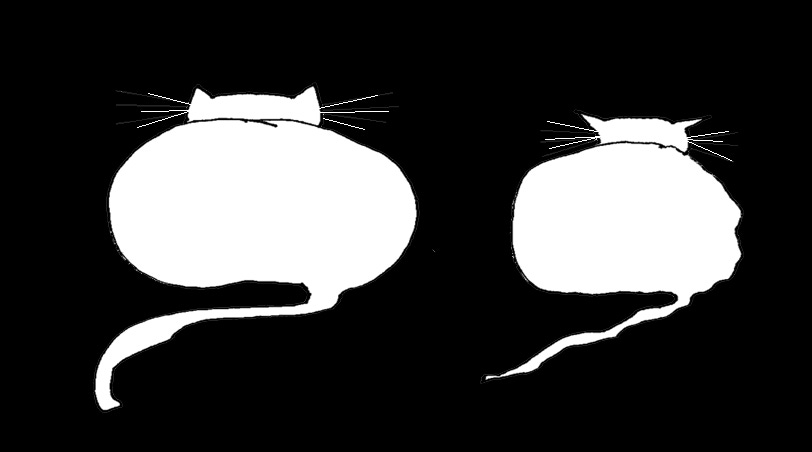

I could always guess what my two cats were thinking when I saw them from behind. It was their body language. Unlike Friedrich, I do have trouble drawing. But I was lucky enough to capture their mismatched personalities on first try. These Rückenkatzen became the template for my weekly cartoon Catspeak at 3 Quarks Daily: Two cats with two very different outlooks on life—the clueless optimist who’s shocked at every piece of bad news and the world-weary cynic who expected it all along. It’s all there to be read in their ruckfigures. Thank you, Caspar.

My other essay Nature’s Emissary: The Art of Caspar David Friedrich is at 3 Quarks Daily.

We definitely need a word for it! I think I’ve mentioned this to you before that something that I truly love to look at is people in a museum looking at art and I always feel like the image of them from the back speaks volumes about the emotional response to the art and I have a folder on mycomputer of these kinds of pictures. The other is people taking communion in a church when they walk up to the altar and watching them from behind, each person looks different as they approach and there’s something about it that tugs at my heart.

Wonderful.