This morning, as I sat outside listening to Bach with open earbuds, an old familiar sound nearby made me put Johann on hold. It was the courting song of a male Turdus merula merula—aka Merle, European Blackbird, or Amsel (in Germany). A Bach among birds, the merle’s troubadour outpourings are unrivaled in their originality and broad spectrum of melodious and rhythmic invention—many suitable for musical notation.

The little fella was performing for his someone—proud and loud. I was overjoyed to listen in, such concerts having become a rarity.

The following essay, written in 2017 for 3 Quarks Daily, now fills me with sorrow. Spring has become a lot quieter in the intervening years. The boisterous melodious merles in my neighborhood have been decimated by the usutu virus. What I once wrote as a celebration could soon serve as a eulogy to these disappearing musical geniuses of the natural world, who deserve a better destiny—not least for having entertained us so well.

Haydn In The Jungle Out There (2017)

First, the jungle out there: Recorded at 4 a.m. in May 2017.

Sound familiar? Hint: It’s not the clatter of journalists in a feeding frenzy over the latest insanity to emerge from the White House. Just an ur-Twitter storm here in Mitteleuropa at 4 in the morning, recorded from my balcony.

Ever since November 9, 2016 I’ve been looking for a parallel universe that could be explored without any reference points to a reality I know all too well. Something immersive, challenging, ongoing, but above all distracting. And presto, the genie of nature answered my wish. On the morning of March 15, [2017] I was awakened by birdsong outside my bedroom window–not just any old chirp-chirp, but the loud crystal-clear melody of a turdus merula merula or European blackbird. The concert season officially began that day, and would last until mid-July. Curtains up on a parallel civilization right outside my window.

The European blackbird (of the four-and-twenty variety) has a PR problem. It’s officially called the turdus merula merula, (no, not Latin for turd), aka the common blackbird. The problem with ‘blackbird‘ is that for much of the world, the name is generic, conjuring up visions of crows, starlings, jackdaws or other birds of the color black.

The turdus merula merula, however, is no generic bird, and though common, it is uncommonly gifted. Matte black, plump, with a bright yellow beak, it is unknown in the Americas, and not related to crows or ravens or starlings. Brits call it blackbird, Germans call it Amsel. In Scotland and in France it’s known as ‘Merle’, a pleasing syllable evoking an old Hollywood goddess (Oberon) or a cool country warbler (Haggard). The merle belongs to the true thrush genus of the thrush family, known for musical talent in many of its variations.

The merle is so ubiquitous in Europe that it’s nearly impossible not to hear one between March and July. The national bird of Sweden, (with 2 million brooding pairs), they cover the continent (62 million brooding pairs), and have even been introduced to Australia. Good choice. Starlings were introduced to America in the 1860’s by someone who should have known better. Had he released a few merles into Central Park that day, America would be better off for it.

What makes the merle so special is its song. No one recording can ever do it justice because every male of the species composes his own music—not just one tune or leitmotif, but a medley of whistled clarion melodies, each no longer than one or two measures followed by a silence of two or three seconds as they wait for an answer. In the morning when the one closest to my window starts to sing, I can hear another merle in the distance, mimicking the song I’ve just heard. [Below, a merle from Vienna]

They not only tweet (That’s their job, unlike others who shall remain nameless), but also share their tweets and retweet them down the line. They learn each other’s songs, contributing to a vast catalog that plays out over kilometers of tree-lined streets and bushy gardens.

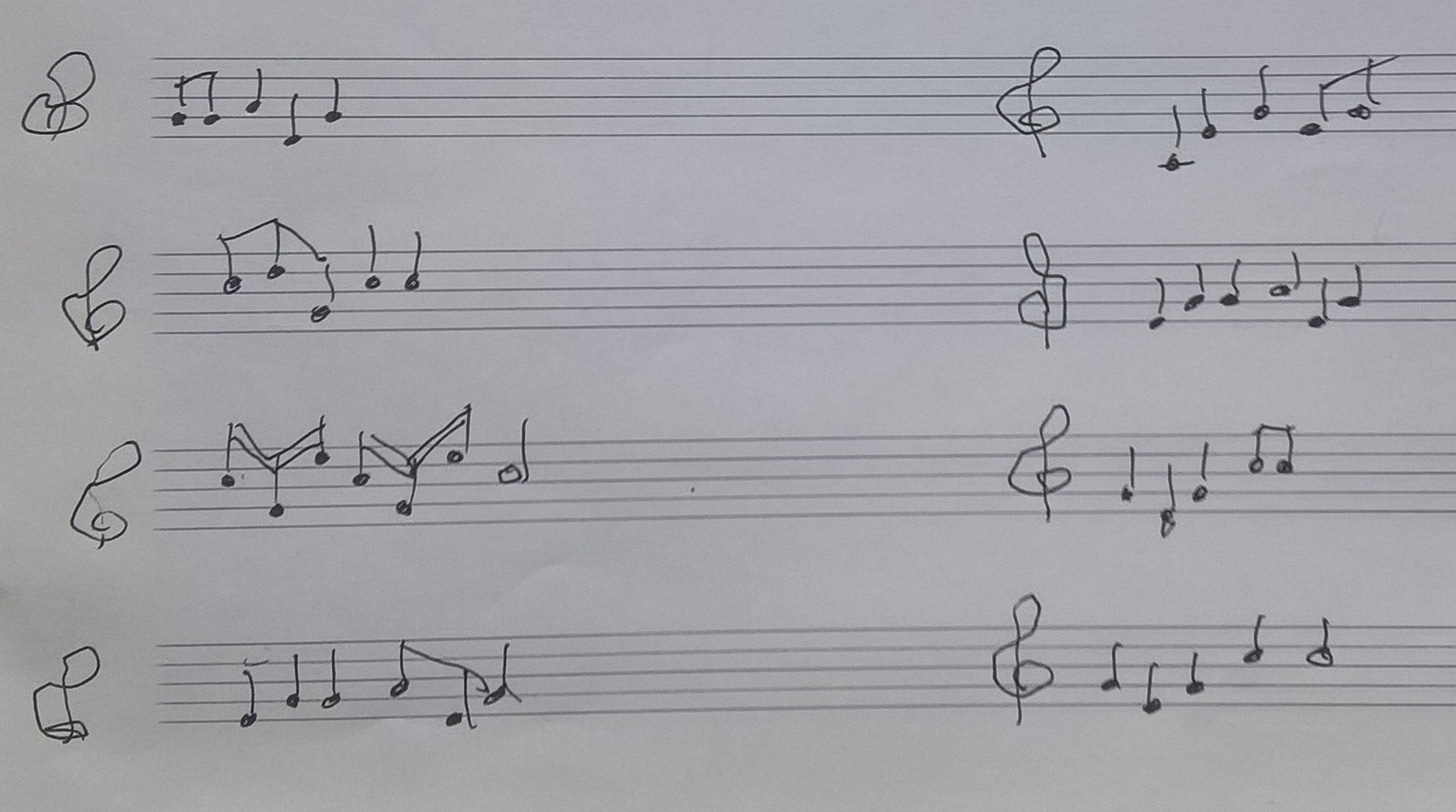

I began to record them with my cell phone and to write down each new tune as I heard it, becoming the amateur avian Alan Lomax of this pocket of Upper Bavaria. So far, I’ve transcribed over 30 separate phrases, some of which could provide the opening bars to a sonata by Haydn, Mozart or Salieri. Olivier Messiaen loved merles. So did Richard Strauss. So did the Beatles (even though merles don’t ‘sing in the dead of night’).

In the tree-lined neighborhood where I live there are hundreds of merles. They sing all day long, from 4 a.m. to nearly 10 at night, with a few breaks in between. They are the first birds to wake up and the last to go to sleep. (When do they eat? When do they feed their young, three broods in three months? I suspect the female does all the work.)

I call them ‘the kids’. ‘The kids have gone to bed,‘ I say around 10 pm when an eerie silence falls over the town. ‘The kids are cookin‘!’ I say when they all sing at once. The merle who routinely stands atop an apartment building across the street, lording it over everybody with his combination of melody and percussive ‘sha-boom, sha-booms, doo-wa, doo-was and cha-CHA-chas,’ is a special friend. When he didn’t show up one day, I began to worry he’d been felled by a cat. But no. After a mysterious two-day absence, he was back at his post on top of his world.

I’m not an ornithologist. I’m not even a bird-watcher. Living in what seems like a vast aviary is like living in a foreign country without knowing the language or the mores. I didn’t set out to study them, I simply wanted to understand them. This is what I’ve learned in the last three months (between acrid doses of Trump lore blasted from the internet):

• They teach their young between 4 and 6 a.m. Each leitmotif is answered not only by a distant rival, but also by nearby fledglings in squeaky karaoke style.

•They shut up between 6 and 10 a.m. giving other birds (sparrows, magpies, tits, chickadees, turtle doves) a chance to get a prosaic word in edgewise. I assume this is when merles forage, eat breakfast and feed their young.

•From 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. they sing and sing, but also whoop, catcall, whistle, chuckle, and squeak in a breathtaking range of sounds between early music instruments and a Moog synthesizer. To write this article I had to close myself off, shutting the windows just to concentrate. Sometimes I am so overwhelmed by the variety of sounds they make that I have to play Schubert Lieder on ear buds to remind myself that I’m human after all. Listening to their ever-expanding repertoire is almost physically painful when I realize that I will never understand it, never be able to record or transcribe all their new achingly beautiful compositions.

•In spite of their numbers, merles don’t swarm. They are a society of lyrical individualists living side-by-side, who communicate with each other by sharing what’s on their minds, without ever succumbing to a mob mentality. It’s difficult not to anthropomorphize with terms like ‘happy’, or ‘utopian’, especially when the occasional whistled ‘Whoa!’ comes across as an ode to joy. No pecking order sullies their avian democracy or peaceful coexistence.

•Just like us, they not only sing, they also converse. What they’re saying is off-limits. It could be anything from ‘The worms are better at the Schmidt house.’ to ‘I’ll give you the moon if you answer my call.’ It could even be, ‘If you steal my song one more time, I’ll break your beak!’ I’ll never know.

What I do know is that sometime in July they fall silent. After that I’ll have to find some other distraction. They’ll still be around after that, hopping around someone’s front garden digging for worms, or chasing each other from bush to bush. I’ll walk past a merle and greet him, as usual. ‘Hi, kid’.

The merles, Trump and I all have one thing in common: None of us has more than 24 hours in a day. The merles use theirs to fulfill their biological destiny, Trump uses his to spread mayhem, and with the help of the merles, I am using mine to replace horror with wonder.

Thanks, kids.

This is incredible! I can’t believe you saw my poem, too! Such serendipity or whatever!!! I love to listen to them, and they are such pretty birds with this incredible repertoire. Oh, I just saw the most stunning black and white woodpecker earlier, with a splash of red either on his tail or underbelly. I live in quite an isolated area so the birds are very happy here! Thank you for commenting on my post! ❤️❤️🤗🤗

Beautiful.