Before I can celebrate painter Caspar David Friedrich’s bigly 250th birthday next month, I’ll have to confess to pilfering the Rückenfigur* from one of his most iconic paintings last week—for an illustration at the top of my first Substack post.

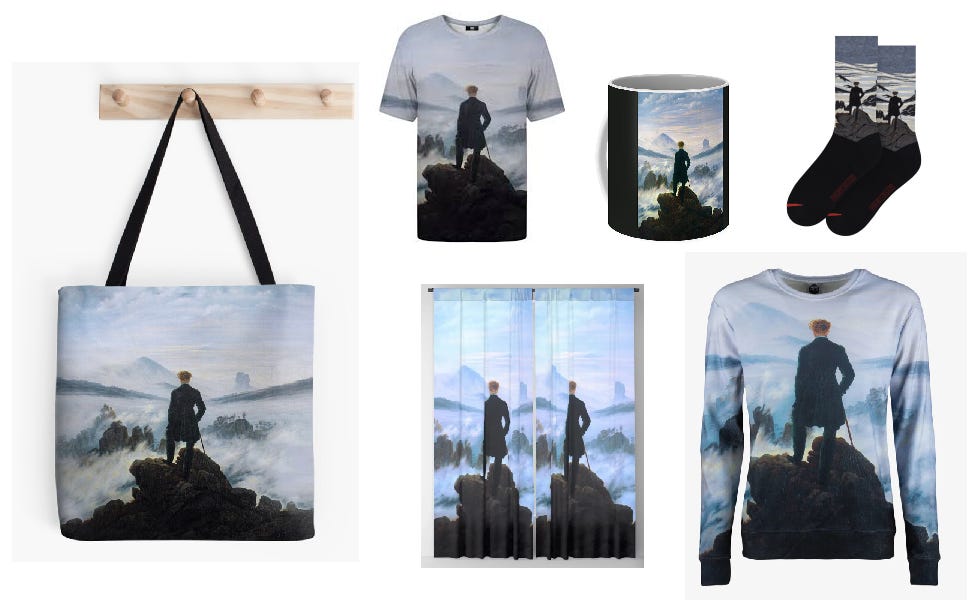

I indulged in this transgression because so many before me have helped themselves to the myriad tantalizing possibilities that Wanderer above the Sea of Fog has to offer. Even an artist like Anselm Kiefer was unable to resist the urge to troll this ambiguous icon of Romantic art—long before Richard Dawkins’ gave birth to the neologism ‘meme’, long before ‘memeing’ became the casual pastime it is today.

If you don’t believe me, do a search for the Friedrich painting in Google images: You may find a few views of the real deal—on art sites or Wikipedia. The rest of the page is filled with images that have been manipulated, often for humorous effect. The volume of memes is overwhelming, each new mutation an assault on the original, even if a few are clever or beautiful. Even the august Frankfurter Allgemeine rolled one out last week, as an illustration for an article about early retirement.

In my defense, I didn’t alter the painting. I merely kidnapped the Rückenfigur for a few hours, leaving behind the rocky promontory and the sea of fog. It’s no excuse. I’m still guilty of trivializing Friedrich for my own purposes. Incidentally, having him stand as an observer in front of Whistler’s Nocturne in Blue and Silver, gave that painting a justification it didn’t deserve on its own—adding a much needed interruption to the yawning gray expanse of the Thames at dusk.

Why do we allow ourselves to desecrate works of art for light entertainment? When did we become so callous? Is it a form of self-destruction to sacrifice the best of our culture to minor fits of childish humor or facile juxtapositions?

Here’s why it matters. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is a painting I once loved. Now I hate it. It has become a tiresome cliché, a misinterpreted paean to the Me Millennium, to the precious pretensions of our age and our notions about individualism. I hate seeing it everywhere, overused and abused, taken hostage by the Zeitgeist.

Ever since images could be digitalized, it’s been open season on whatever masterpiece happens to grab the collective fancy. The Mona Lisa has been put through the icon-smasher since the start of photoshopping. The playing field is leveled, with every sacred cow of the art world now fair game for merry memesters with their pixel-popping toolkits.

The side effect of this routine exploitation of what was once a rare gem, is that one begins to hate the original. I was never a fan of the Mona Lisa to begin with, or its waxy sfumato, but I wouldn’t wish any work of art such an onslaught of cheapening mutilations.

I first saw Wanderer above the Sea of Fog at the Hamburger Kunsthalle in the mid- nineties. In a 2016 essay, I wrote: ‘This wanderer, who could well be the blondish Friedrich himself, now takes center stage in a work that offers so many interpretations, both positive and negative, and so many metaphors jostling for attention, that one is compelled to apply one’s own mortal coil as a foil against which to examine it.

The memesters seem to be doing just that, applying their ‘mortal coil’ to the image in all sorts of wicked and wonderful ways.

Even in its pristine state, Wanderer has become an itinerant ‘poster child’—doing for Romanticism and the Romantic experience what the opening bars of Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra once did for space travel and corporate grandiosity. I love Richard Strauss too, but I’ve grown to hate those opening bars as well.

I’d like to think that memes will go out of fashion someday, but then I remember how enticing it is to plunder a work for yet another ‘facile juxtaposition’. And even if we grow weary of the repetitive mischief of memes, there’s always AI around the corner to really shake things up.

Masterpieces are on too many bucket lists to be derided into oblivion. Lesser known works will be mercifully spared such infamy. Art may be dishonored by the casual abuse of memes, but it will endure. Memes cannot ruin art. They may even—in some convoluted way—dignify art’s role in our cultural lives.

As for me, I can’t promise I won’t someday be a repeat offender—unable to resist looting one image in the service of another. So in advance, mea culpa.

*Figure seen from behind

Umberto Eco has a great essay about seeing something like seven wax copies of the Last Supper just on a trip from LA to San Francisco. I think Hokusai's The Wave is another --maybe Starry Night? It becomes so iconic almost like a memorized poem. What I found personally so unexpected was my reaction to seeing the real Leonardo in Milan--not being a fan of Leonardo and not a fan of Last Supper iconography–and of the three possible Last Supper subjects, my least favorite is the one Leonardo chose: that of the betrayal-- I was so surprised to find myself moved to tears. It was like the work was bearing down on me... so I don't think it necessarily removes the power of the art because the art has its own power but yeah.... memes!!

Brooks- I never thought I’d be thinking about art and AI in one breath so this is all interesting to me. Enjoyed the piece, especially when you wrote: “And even if we grow weary of the repetitive mischief of memes, there’s always AI around the corner to really shake things up.” 🙌🏼