Jean-Luc Godard once inscribed a photo of himself standing in front of a blank white screen: “This is the surface, Brooks, and that’s why it’s deep.” At the time, I was skimming the surface, darting from one life experience to another without stopping to sink down or dive deeper—or give his words much thought. Wordplay was our swordplay, but this one sounded like a facile paradox.

(As a 9-year-old with not enough movie-going experience, I could have shot back: “This is the surface, Jean-Luc, and it’s a grande illusion”—as I waited in vain for Marlon Brando to emerge from the back door of my local movie theater after a showing of Desirée.)

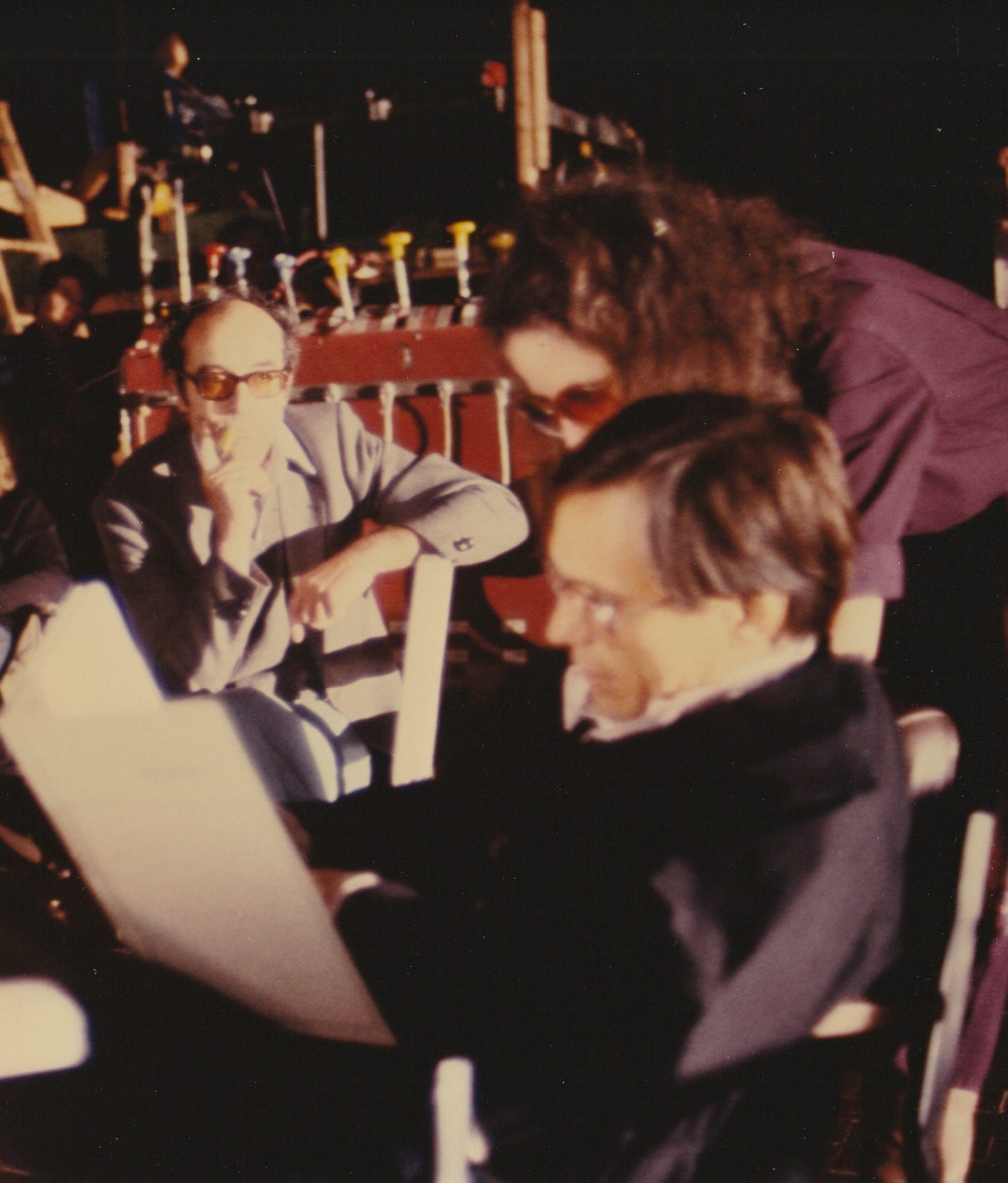

As a man of cinema, Godard must have thought of that great cinematic paradox, the flat screen and the depth of field that miraculously occurs when a film is projected onto it. In the photograph, taken at Zoetrope in 1981, he stands in front of the blank screen he would soon be using for a shadow dance to the opening bars of Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D Minor, defying the double-entendre of flatness and cinematic depth with a chiaroscuro ballet in front of the screen: A crane operator partnering his crane as it maneuvers the camera, cameraman and focus puller slowly up, over, and then back down again in a graceful pas de deux silhouetted against the flat white surface—a two-dimensional triumph.

How subversive that this transcendent moment was filmed on the soundstage where the glittering streets of Las Vegas had been built for Francis Ford Coppola’s One from the Heart. The crew was hired for a Saturday from that bigger film, for a series of test shots I co-produced for Godard in preparation for his feature film Passion. The Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky played ‘the director’, Academy Award-winning cinematographer Vittorio Storaro played himself, and I played the ‘nagging producer’ in the first scene—a cameo Godard sprang on me five minutes before shooting. (Swordplay would have come in handy.)

In the fourth scene, as Godard piped Mozart over the loudspeakers, and the camera rolled, a cathedral hush permeated the vast dark interior of the soundstage. The elegant middle-aged crane operator began to move in front of the white screen with the assurance of a dancer, ‘choreographed’ by Storaro. When the music faded out, the hush prevailed. No one—not the crew, the visitors, or the cast—had ever seen anything like it. It's a shot that never fails to move me to tears. Surface magic, deep beyond words. Now I understood Godard’s paradox.

Too often surface is a euphemism for superficial. But living on the surface makes it easier to move around. The assumption that one has to dig or dive deep to find meaning, inspiration, or even treasure is not reliable. Mastery can emerge from the cross-pollination between knowledge, experience and creativity, or be achieved by moving far afield over a surface, like the gerridae, those insects who walk on water, always finding what they need on top, not deep down. Knowledge is like that body of water: You can dive down into it, but to see clearly you must eventually rise to the surface. If you stay on the surface, you may know less about one thing—but more about a lot of things.

What motivates the glide across a surface? Is it the endless pursuit of knowledge in bits and pieces? Or a bucket load of experience? Or is it a yearning for aesthetic overwhelm—one way to describe the wave of awe that occurs when confronted with the sublime? For one who grew up solitary, ‘aesthetic overwhelm’ can compensate for a lack of social engagement. In its way, such a response can be as addictive as Mt. Everest is for climbers, only less dangerous.

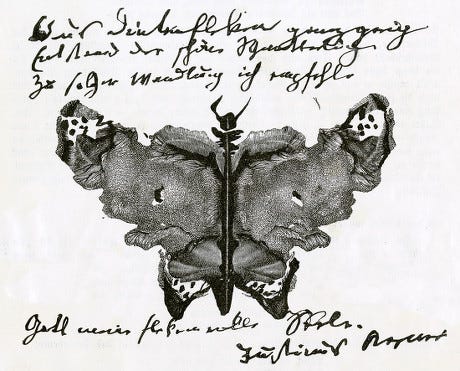

I admire the artists and scientists of past centuries who were polymaths—multitasking on a grand scale. Take the poet Justinus Kerner, whose lyrics were set to music and immortalized by Robert Schumann: Kerner also invented klecksography, the art of turning ink stains into recognizable forms, what Rorschach would later apply to psychological testing. He wrote the first diagnostic paper on botulism poisoning. In his spare time he was a doctor, and author of books about medicine and about animal magnetism.

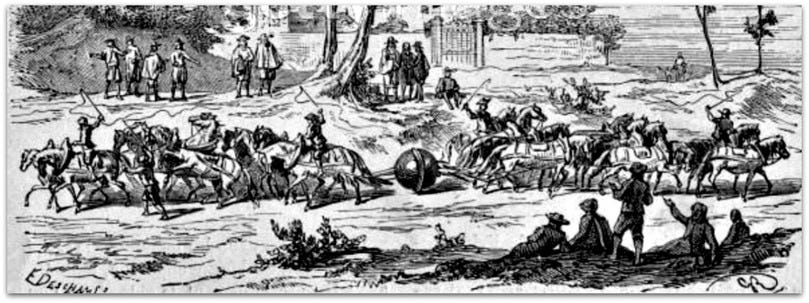

Or Otto von Guericke, Mayor of Magdeburg, politician, jurist, physicist, inventor, who made great strides in the study of vacuum and staged a grand experiment with 16 horses to prove his point.

Or the multifarious Goethe—poet, novelist, scientist, playwright, statesman, philosopher. Strindberg and Schoenberg were both painters, too.

Those who devote their lives to one endeavor, creating masterworks or making discoveries in their chosen field, have established their own version of a perfect life within the confines of a single métier. Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel comes to mind, getting to the bottom of memory on the bottom of the ocean, assisted by the lowly sea slug Aplysia californica and its gigantic nerve cells.

But Kandel, like many scientists of earlier generations, also casts his net wider, to a time when art and science cozied up to one another in fin de siècle Vienna. In his book Age of Insight, he connects his own scientific expertise to the seemingly unrelated topic of visual art and the aesthetic response, reviving that rare juncture of art and science to expand his understanding of the human brain beyond the synaptic level. For him the surface is indeed deep.

I understand the urge to diversify. My interests are polymathic, but I am fickle. In the end, I polish my prose to try to render those interests irresistible to others—and then I move on, lured by the promise of some new edification around the corner, be it scientific, musical, artistic, cinematic, historical or literary.

Surface and surfing have different etymologies, but they both enable broad coverage of terrain and the random discovery of subjects that can launch an obsession—one thing leading to another in a seemingly never-ending reserve of revelations. The internet and additional languages have expanded that surface area, adding multiple choices for future scrutiny.

Finding analogies that reveal the interconnectedness between unrelated subjects—this is the unsung activity of the dilettante, whose playing field is the surface. It can also be a form of survival for a child newly transplanted in a foreign environment. For fun I used to scribble wildly and haphazardly on a page, then set about finding something recognizable in the chaos. When I found it, the application of two dots (for eyes) might turn the chaos into a sweet dog, or a monster, or a smug schoolmaster. There was always something to be found in the chaos—a suitable metaphor for the foreign made familiar.

Godard himself moved across the surface as a scavenger going after diverse elements to work into his films, or an alchemist in search of the stuff of chemical reactions. In Passion, he ventured into the ‘cinéma muet’ world of art, recreating tableaux vivants of paintings by Goya and Rembrandt. None were as beautiful as the test shot version of Le Nouveau-né by Georges de La Tour at Zoetrope that day—mother and nurse played by Hollywood extras. For all his tinkering with the properties of cinema, Godard was also its poet.

Ironically, Godard enabled me to waive my exclusive interest in cinema. After working with him I grew closer than ever to music and art.

A few years later, I heard Mozart’s Requiem again, nearer to its source—reliving that ‘cathedral hush’ in the Salzburg Cathedral at a memorial service for local Herbert von Karajan. As I listened, I imagined Godard’s crane soaring up toward the ceiling of the dome and across the transept of that gloriously bright baroque interior—a loftier trajectory made possible by an indelible memory.

A lifetime on the surface is hard to change. I’ve begun to delve deeper into things, and to create work of my own—resurrecting old mirror neurons that once yearned to master what they mirrored. I now paint with an app, seeing total strangers emerge from my efforts—and occasionally, a deconstructed, surface representation of that chaotic warehouse in my mind.

The search for meaning is a quest for the sublime. An artist finds it within himself—as Godard did. The beholder must seek it out. The starting point is sum ergo cogito, not the other way around. The exquisite always lingers somewhere, as alluring as Everest. Some of us dive deep. Others of us dance over the surface to gather as much as we can. I’m weaving my motley carpet with all the magic I’ve encountered. It’s of no importance to anyone and it doesn’t change a thing. But it makes my life deeply entertaining.

Well, it's important to me! And by the way,that Schoenberg could be a self portrait of Andy. Talk about your connections across the cultures.